Sometimes I can't get out of bed because I get wrapped up in the confluence of my reading, my writing, and my thinking.

It was one such morning. I needed to get up, I had an appointment at 10. It was important.

It's importance, however, conflicted with my need to keep working through images roiling in my mind.

It started with one more headline about refugees being smuggled into Europe, about Germany turning the other way because of a current election, about Macron in France perhaps opening up.

But It was the following lines that hit my eyes:

Thousands more have been stranded in Serbia…

But the migrants themselves told USA Today they don’t want to stay.

“I tried to leave Serbia 17 times,” Jawad Afzali, 17, an Afghan refugee in Belgrade told the newspaper. “Every time, they bring me back here.”

My mind drifted back a couple of years to 2015, when my brother Alex and I were visiting my Cousin Goga in the heart of Belgrade, staying in a hotel near his apartment, across the road from the train station, next to fields teeming with homeless refugees.

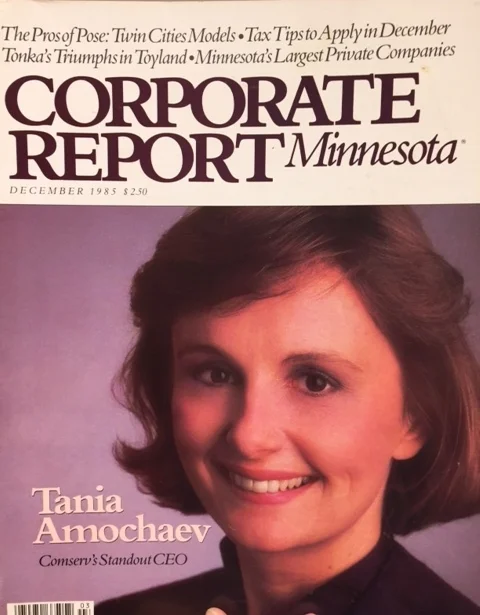

Alex and me with my cousins in their apartment in Belgrade.

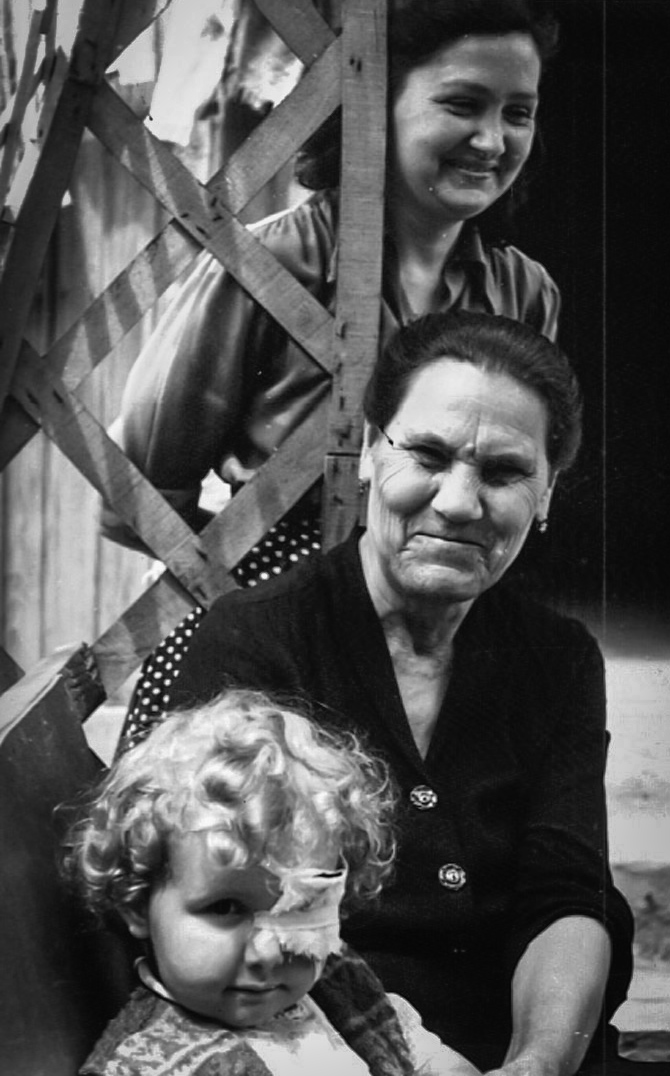

Near an apartment I had often visited as an infant, over 60 years ago, when my family still thought we were safe, when they didn't yet know that being refugees was soon to be in our future again.

An apartment where my cousin had grown up, raised his family, made a successful life for himself. Where divergent histories played out within one family.

The nearby apartment in Belgrade where my family lived when I was born.

My thoughts crept back another year, to when Alex and I had visited Trieste, where we had lived in a refugee camp of old army barracks as children.

On that visit, in 2014, in addition to our first visit together to the memorial for that camp, we spent time in an abandoned dockland, a port driven out of business when the Iron Curtain crashed and East Europeans had free access to the West, no longer needing to sneak into Trieste to shop for those desired Western goods. That abandoned port was home to hundreds of Afghan refugees, and we talked to young Afghanis playing soccer in a makeshift field.

With Afghan refugees, 2014, in an abandoned dockyard at the port of Trieste, now in Italy. When we lived there it was a United Nations protectorate, still being fought over by Italy and Yugoslavia.

And then my mind went back almost 100 years to 1921, when another infant landed in Belgrade, a refugee who had fled his country, Russia, on a crowded ship and spent months in a tent camp on a Greek island on his way there. The same island, Lemnos, where Syrian and Afghan refugees were now living in tents. And the parallels kept multiplying, threatening to choke me, my eyes leaking, my survivor’s guilt mounting.

That final infant was my father, but Belgrade was the end of his family's journey. Serbia was their safe asylum. Or so it seemed, for the next 30 years, until that safe asylum grew unsafe.

My Russian grandfather's grave, in Belgrade, restored by Vladimir Putin as part of a new push to reclaim the Russian Orthodox Church globally.

I'm beginning to understand why I'm struggling with the story I'm working on about my recent travels. Understanding why getting almost arrested in Iran led me to just a hint of understanding about my father's experiences in Belgrade is one thing. Writing about it is another.